Great American Death Masks (from the site)

Posted on Monday, April 26, 2004. “I shall secure him to a nicety if I am so fortunate as to get plaster enough for his carbuncled nose.” Originally from “A Collection of Death Masks,” Harper's New Monthly Magazine, vol. 85, iss. 510, October 1892. By Laurence Hutton.

Washington was as blessed in his death as in his life. He rests still upon the banks of the Potomac, among the people whom he so dearly loved, and among whom he died; and no later administration has ever cared to cut off his head[1] for exhibition on the roof of the Patent Office or the Smithsonian Institute.

At least two plaster casts were taken from the living face of Washington. The first, by Joseph Wright, in 1783, was broken by the nervous artist before it was yet dry; and the subject absolutely, and, it is whispered, profanely, refused to submit to the unpleasant operation again. The second was made by Houdon, the celebrated French sculptor, in 1785, and from it he modelled the familiar bust which bears his name.

The original Houdon mask of Washington is now in the possession of Mr. W. W. Story, in his studio in Rome. He traces it directly from Houdon's hands, and naturally he prizes it very highly. It has been preserved with great care, and of it he says that there is no question that “it was made from the living face of Washington, and that therefore it is the most absolutely authentic representation of the actual forms and features of his face that exists. In all respects, any portrait which materially differs from it must be wrong.” Mr. Story cannot account for the fact that the sculptor opened the eyes of Washington in the mask, except upon the supposition that he did not remain long enough at Mount Vernon to have studied and modelled the eyes for his bust from the face of Washington himself.

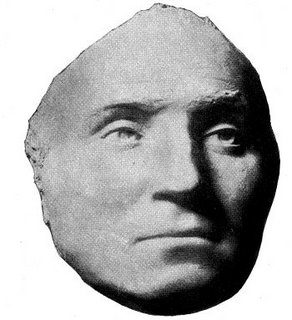

It is but just to add here that Mr. Story says that never, to his knowledge or belief, has a cast been made from the original which he owns. He examined the so-called cast in the Corcoran Gallery at Washington, and he was fully satisfied that, like all the other specimens in existence, it is of no value in itself, and was made from a wornout copy of the bust. The Washington here presented is from a photograph taken by Mr. Story in Rome, and from his own copy of the mask.

When Houdon came to America in 1785 to make the bust of Washington, he was the companion of Benjamin Franklin, and he was, in all probability, the author of this cast of Franklin's face, taken in Paris that year as a model for the well-known Houdon bust of Franklin, which it somewhat resembles. The original mask was sold for ten francs after the death of the artist in Paris in 1828.

The familiars of Franklin have shown that his face in his old age changed in a very marked degree. He was in his seventy-eighth or his seventy-ninth year when he sat for Houdon in 1784-5. Many of the features of the Franklin cast as here reproduced, the long square chin, the sinking just beneath the under lip, the shape of the nose, and the formation of the cheek-bones, are strongly preserved in the face of one of his great-granddaughters living in Philadelphia to-day.

Leigh Hunt in his Autobiography said that Franklin and Thomas Paine were frequently guests at the house of his maternal grandfather in Philadelphia when his mother was a girl. She remembered them both distinctly; and in her old age she told her son that while she had great affection and admiration for Franklin, Paine “had a countenance that inspired her with terror.” Hunt was inclined to attribute this in a great measure to Paine's political and religious views, both of them naturally obnoxious and shocking to the daughter of a Pennsylvania Tory and rigid churchman. Concerning the physical as well as the moral traits of the author of the Age of Reason, there seems to have been great diversity of opinion. To paraphrase the speech of Griffith in Henry VIII concerning Wolsey, He was uncleanly and sour to them that loved him not, but to those men that sought him, sweet and fragrant as summer.

His friend and biographer Clio Rickman, who considered him “a very superior character to Washington,” gave strong testimony to his personal attractions and tidiness of dress; while James Cheetham, his biographer and not his friend, told a very different and not a very pleasant story, in which soap and water ‒ or their absence ‒ play an important part. The former, according to Cheetham, was never employed externally by Paine, and the latter was very rarely, if ever, internally applied.

None of his earlier biographers give any hint as to the taking of this death-mask, nor is it to be found in any contemporary printed account of the death-bed scene. Experts agree that it is the face of Paine, and see in it a strong resemblance to the face in the Romney portrait, painted in 1792, seventeen years before Paine died. It was undoubtedly made after death, by John Wesley Jarvis, the painter, who was at one time an intimate of Paine's. He studied modelling in clay, and made the bust of Paine which is now in the possession of the Historical Society of New York.

Concerning this bust Dr. Francis, in his Old New York, wrote: “The plaster cast of the head and features of Paine, now preserved in the gallery of arts of the Historical Society, is remarkable for its fidelity to the original at the close of his life. Jarvis, the painter, then felt it his most successful work in that line of occupation, and I can confirm the opinion from my many opportunities of seeing Paine.” He added that Jarvis said, “I shall secure him to a nicety if I am so fortunate as to get plaster enough for his carbuncled nose,” which was not a very pretty speech to have made under any circumstances, particularly if the bust was a posthumous work.

Of Lincoln, as of Washington, two life-masks were made ‒ one in Chicago in the spring of 1860, by Mr. Leonard W. Volk, and here reproduced; one in Washington, by Mr. Clark Mills, about five years later.

Mr. Volk, in the Century Magazine for December, 1881, gives a pleasant account of the taking of the former. Mr. Lincoln sat naturally in the chair during the operation, watching in a mirror every move made by the sculptor, as the plaster was put on without interference with the eyesight or with the breathing of the victim. When, at the end of an hour, the mould was ready for removal ‒ it was in one piece, and contained both of the ears. Mr. Lincoln himself bent his head forward and worked it off gradually and gently, without injury of any kind, not withstanding the fact that it clung to the high cheek-bones, and that a few hairs on his eyebrows and temples were pulled out by the roots with the plaster.

This is, without question, the most perfect representation of Mr. Lincoln's face in existence. I have watched many an eye fill while looking at it for the first time; to many minds it has been a revelation; and I turn to it myself more quickly and often than to any of the others, when I want comfort and help.

Notes

1. cut off his head ‒ an allusion to Oliver Cromwell, whose body was exhumed in 1661, hung, drawn and quartered. The body was thrown into a pit, and the head displayed on a pole outside Westminster Abbey until 1685.

This is Great American Death Masks, an essay and a subject, originally from October 1892, published Monday, April 26, 2004. It is part of Death, which is part of Harper's Archive, which is part of Harpers.org.

RelatedFounding FathersNavigate by HierarchyPrev: [First in section]Next: A Child's First Impressions of Death

Up: Death Navigate by Time of PublicationPrev: Lingvo EurocraciaNext: Weekly Review

Permanent URLhttp://harpers.org/AmericanDeathMasks.html

No comments:

Post a Comment